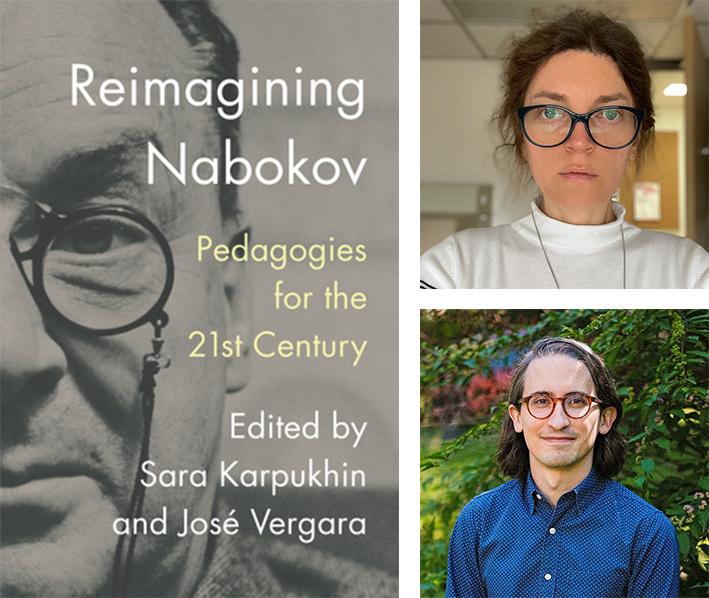

Slavic Studies congratulates 2015 and 2016 PhD alums Sara Karpukhin (UW-Madison) and José Vergara (Bryn Mawr) on the open-access (free!) publication of their co-edited volume Reimagining Nabokov: Pedagogies for the 21st Century (Amherst College Press, 2022). The volume features contributions by 11 teachers of Nabokov who describe how and why they teach a notoriously difficult—if not also problematic—writer to 21st-century students. Contributors detail how developments in technology, translation, and archival studies as well as new interpretive models have helped them address urgent questions of power, authority, and identity. Both editors regularly teach Nabokov at their respective institutions—and Slavic Studies at UW-Madison is fortunate to have Dr. Karpukhin among its instructional faculty.

Dr. Vergara’s chapter in the volume is titled “Good Readers, Good Writers: Collaborative Student Annotations for Invitation to a Beheading.” In addition to writing the volume’s introduction, Dr. Karpukhin contributed a chapter titled “Nabokov, Creative Discussion, and Reparative Knowledge.” Another UW Slavic PhD alum, Matthew Walker (Middlebury College), also wrote a chapter titled “Teaching Poshlost‘: Texts and Contexts.”

We interviewed the co-editors to find out more about how the volume came to be and their hopes for its reception.

Congratulations to you both on the publication of the volume! What inspired you to collaborate on a project devoted to reimagining Nabokov from a pedagogical perspective?

JV: Thank you! The volume grew out of a series of conversations Sara and I have had over the years about teaching Nabokov—our challenges and successes—and our aspiration to engage with colleagues about how else we might teach such a complex writer’s works. Personally, I was eager to pick up new tricks, particularly when it comes to his less frequently taught works. It also struck us that college education has shifted dramatically in the last ten years for many reasons, and it would be worth exploring how Nabokov fits into these paradigm shifts—or not.

SK: I agree! I wrote my dissertation on Nabokov, but teaching him was in an important sense a re-education. I began to reflect on the implications of this new experience when I had the good fortune to discuss it with José. Our shared sense, it turned out, was that it could be a symptom of something bigger than our personal adjustment to the role of educators. The volume took a few years to come to fruition, but other colleagues offered a diverse range of inspiring new approaches that I think confirmed that original sense. I hope, generally, that the project will create opportunities to strengthen the community of scholars, instructors, and students and readers of Nabokov.

The volume’s focus is on the teaching of Nabokov, which raises the question of how the contributions might also be read as contributing to scholarship on Nabokov. How do you see this?

JV: Research and teaching are inextricably intertwined. I believe that our volume proves that. Several of the contributions grew out of research on Nabokov being implemented in the classroom. Likewise, some contributors wrote about their experiences teaching Nabokov through various research methods, such as digital humanities or archival work, and sharing those approaches with students to achieve new insights into his work. It all feeds into itself. I think one thing that most Nabokovians share is a desire to share his writing with others; often that takes the form of teaching. So, it makes sense to me that these essays often say just as much as scholarship on Nabokov, as they do on the teaching of him.

SK: I, too, believe that teaching is one of the most powerful heuristic tools at our disposal as scholars and researchers. When we reimagine our teaching, we reimagine our fundamental conceptual grasp of the subject, and vice versa. One of the most exciting aspects of this collaborative volume for me was the emphasis on the communal role of knowledge that our contributors adopted in their individual ways. To see that was almost like a moment of professional self-discovery, for me, and it certainly clarified the direction of my research.

What do you hope its reception will be in the field?

JV: Universal acclaim and adoption! One can dream, right? Speaking seriously, aside from a position reception, I hope the volume serves as a launch pad for new and revised approaches to how we teach Nabokov in ways small and large. I love experimenting in the classroom—as in my research—and I find it so helpful to read about what others’ have done. Hopefully, our volume can do the same. There’s no single right way to read Nabokov, but I think Sara’s introduction in particular addresses the significance of context and shifting values beautifully. It’s important, I think, to present our students with a wider picture of Nabokov with both his achievements and his social and cultural lacunae, his innovations and his “faults.” Aside from that, these essays are about Nabokov, but I hope that the methods they describe will also inspire ideas for teaching other writers as well.

SK: The hope for a wide engagement with our project in the field and beyond, of which José speaks, was definitely there for me, too. We wanted to start the kind of conversations that have historically been in rather short supply in the field, as far as I can see. Whether we call these conversations revisionist or radical or reception-oriented, we know that there’s a demand for them within the discipline. Last year, for example, a number of Nabokov scholars, including José, collaborated on the volume Teaching Nabokov’s Lolita in the #MeToo Era. My expectation is that colleagues will receive our project as an invitation to continue these discussions, among themselves and with their students. But I love how José describes his attitude to teaching and scholarship as experimental, and I want to echo his words regarding the methods. The volume is about changing ways we acquire, share, and valuate knowledge as much as it is about Nabokov. To open any academic knowledge to questioning is to make the whole enterprise of academia productively unsettled, and hopefully make it more self-aware, more joyful, more philosophically if not politically accountable.

Do you plan on—or could you imagine—working on a volume about other Russian (or Slavic) writers who might also benefit, in your opinion, from pedagogical reimagining?

JV: That’s an excellent question. Of course, options are probably limited to “major” authors based on publisher demand and interest, but a couple ideas come to mind from my research and teaching: volumes (with translations?) on ecologically-minded texts and on prison writing. I think the field is ripe for reimaginings, but I’d perhaps be more interested in considering less frequently taught writers and offering insights into how they’ve been incorporated in syllabi, approaches to teaching them, and successful activities or discussion strategies. In any case, I look forward to future collaborations with Sara!

SK: Same here! I loved working with José and our wonderful contributors and our great team at Amherst College Press. The idea of continued collaborations sounds ideal to me! As for reimaginings, I tend to have some reservations towards “major” authors in the Russian canon, but I understand the appeal of the thematic approaches that José mentions. I dream of the circumstances, for example, when I have the time to think and talk to José and other colleagues about connections between various queer communities, especially in 20th-century Russian-speaking diasporas.