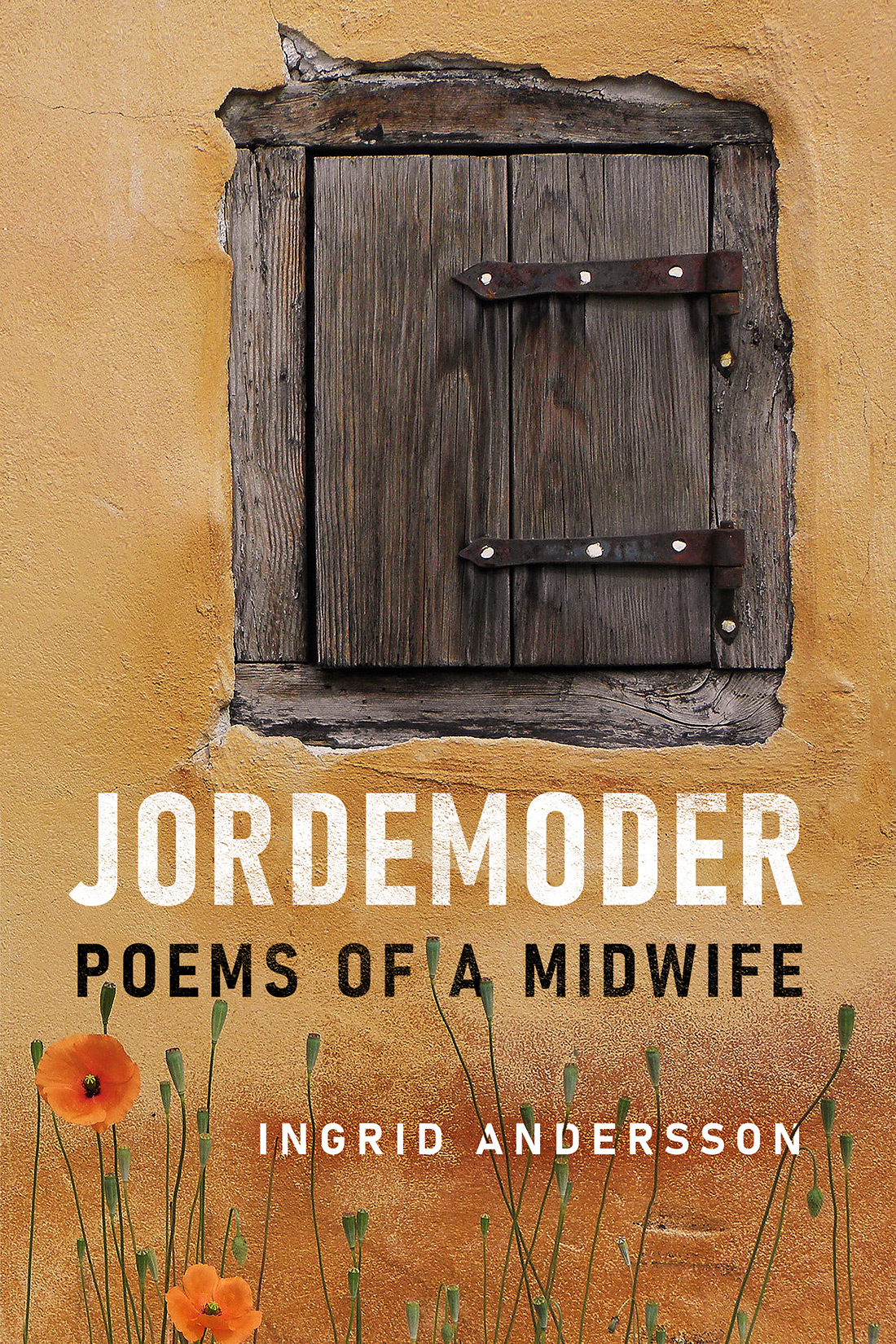

Ingrid Andersson – Joredemoder: Poems of a Midwife

Alumni Ingrid Andersson talks about her recently published poetry book Jordemoder: Poems of a Midwife and the journey that has led her to writing it.

Having a Swedish mother, Ingrid Andersson was raised with Swedish ideas on birth and motherhood. Growing up in the U.S. alongside Swedish culture, Andersson became very interested in the differences between the ways in which both countries treat birth and pregnant women. Andersson now works as a midwife, and believes in developing a trusting relationship with the women she assists, as well as building safer and more comfortable spaces for pregnant and birthing women in the U.S. She has also been passionate about poetry since childhood, and thus her new book, Jordemoder combines both her interests.

Jordemoder, an old Swedish term for “midwife”, translates to earth-mother. In Andersson’s words, “Jordemoder is a word that reflects my practice as a midwife and as a poet, and that is why it seemed right for the book title. I could use words such as “ecological midwife” and “eco-poet,” but there’s nothing special or trendy about what I do – it’s the same messy world of complicated emotional and physical processes, blood and other bodily fluids that it’s always been, and we’re all in it together.”

After graduating from UW-Madison with a degree in Scandinavian Studies, German, and Anthropology, Andersson relocated with her family to Sweden, where she and her husband could spend time writing and her son would experience Swedish education for some time. She currently lives in Madison with her husband, dogs, chickens and bees, and continues to work as a midwife.

Andersson’s upcoming book will be released in April, with a launch party by A Room of One’s Own bookstore. To learn more about the release of the book, visit Andersson’s website: ingridandersson.info

We interviewed Ingrid to learn more about her book, experience as a midwife, and how the UW has shaped her career.

Question: Can you tell me about your story with midwifery and how you got to the position you are in today?

In my world, everything starts with mothers. My mother was born at home on her family’s farm in Sweden. In Sweden, midwives have always been and still are the primary health care partners for pregnant and birthing people – unless complications develop that require a specialist. But in 1960s’ Chicago, where I was born, the cultural norm was to tether a woman’s ankles and wrists to a hospital bed, while she labored with a doctor and nurses she did not know, under the effects of an injected amnesiac. The drug scoplomine took away a woman’s memory of labor and birth without actually taking away the pain. So maternity wards were filled with screaming flailing women. Before the drug took effect, my mother recalls the screaming (which may have included her own) and that a nurse told her “shut up, you don’t know what real pain is.” I wish I could say that my mother’s story was the exception, but it was the rule for thousands upon thousands of American women. My mother’s story was a backdrop for my own life experiences and education. Before I knew it myself, I was on a path toward midwifery, and home birth in particular.

Unfortunately, America is still not a mother- or family-friendly country, and it soon became clear that activism would be a necessary part of my work. After 20+ years of practice as a nurse midwife, participating in the public health Fetal & Infant Mortality review team, founding nonprofits that support breastfeeding and full-spectrum pregnancy options, working to protect natural and built environments, I believe that restrictions, threats and stresses placed on pregnant and parenting people in America today are as burdensome as ever!

Question: How has Swedish culture contributed to your career and this book of poetry?

After graduating from UW-Madison with degrees in Scandinavian Studies, German, and anthropology, I planned to pursue a Masters in anthropology, studying living folk arts in Sweden. But after spending time living and working in Norway and Sweden, what captivated me above all were the differences in quality of life. People didn’t lose their health care or go bankrupt when they lost their jobs. People didn’t have to suffer jobs they hated just for “the benefits.” Holidays and family leaves were paid and lasted longer. Adult classes were free or affordable. Nature was never far away, and all were invited to wander in it. Food was healthier and coffee was stronger. Even now, Sweden still feels more clear-headed, humane and livable to me than America. When my Swedish-Finnish husband and I began to plan a sabbatical, Sweden was a natural choice. We would devote a year to our shared love of writing, while our son would experience a local Swedish school, and our dogs would revel in scents of sea and forest and Swedish dogs.

Question: How did the idea for this poetry collection begin to take root? Did you plan for it to become a book?

I had written poetry since elementary school but did not think I’d be writing poetry on Gotland. My plan was a year of freelance research and writing around reproductive rights and access in Sweden. I had left a Madison where Planned Parenthood had been on lockdown, after a man entered the clinic with a gun and ended up killing himself across the street. Another man had been arrested for intending to plant explosives at the same clinic. Doctors I knew went to work in bullet-proof vests. I wanted to show Americans what a more family-friendly society could look like, up close and in detail. I did write one article, published in the Progressive magazine, that attempted to do this.

Then, something changed – I became less interested in the fight and more interested in the bridging. The poet Eaman Grennan says, poets are like string theorists in some ways, trying constantly to bring the macro and the micro into a single focus. I believe that Sweden is a place that fosters openness and bridging. Both my book and my present life as a practicing poet were born on Gotland.

Question: What role do you believe midwifery and home births have on the environment, and how do you think women can feel more comfortable when giving birth at home?

Jordemoder, as you know, is an old Swedish word for “midwife.” (It’s still the word used in Danish.) It means earth/land/world-mother. (If anyone has a good source on where the word came from, I would love to hear it!) Jordemoder is a word that reflects my practice as a midwife and as a poet, and that is why it seemed right for the book title. I could use words such as “ecological midwife” and “eco-poet,” but there’s nothing special or trendy about what I do – it’s the same messy world of complicated emotional and physical processes, blood and other bodily fluids that it’s always been, and we’re all in it together. The pregnant people who work with me are not my “patients,” and I am not their “provider.” Hour-long visits in my home office, or in the pregnant person’s home, allow me global and individualized health assessment and response and gift us both a trusting and meaningful relationship – whether birth takes place at home or in hospital.

Question: Do you think the perception of midwifery and home births differs between America and Sweden? What can both countries learn from each other?

My husband’s sister sent us an article from her local paper last year. It quoted an obstetrician warning pregnant people not to choose home birth in response to hospital policies and pressures during Covid. While Sweden is remarkably science-based in many ways, its policies around both home birth and Covid have seemed a little off-track to some of us. We know that 1. labor and birth typically are not illness events, and 2. lack of familiar trusted support people can negatively affect outcomes. For healthy pregnant people who feel safe in their home and can access a qualified midwife, as well as hospital services if needed, home birth is a rational choice. It is typically a deeply satisfying option that places less stress on finite resources, even during non-pandemic times. In America during Covid, home birth requests have soared, but most insurance plans still don’t cover it. Several poems in the book show how a universal health care system such as Sweden’s is key to a vision for reproductive justice.