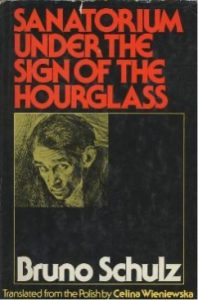

Current Slavic PhD student Victoria Buyanovskaya’s article on Bruno Schulz, titled “Turning Back Time to Keep Writing: Melancholic Memory and the Making of the Modern(ist) Self in Bruno Schulz’s Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937), has been published in the most recent edition of the academic journal The Polish Review. The article reads Schulz’s 1937 text Sanatorium pod klepsydrq through the lens of both Freudian and post-Freudian perspectives on melancholia, and the analysis focuses in particular “on the dynamic boundaries between the ‘real’ and imaginary spaces that the narrator constructs, balancing and at the same time de-stabilizing the notions of separation and encounter, distance and immersion, determinacy and freedom.”

We interviewed the article’s author to find out more about her interest in Schulz.

How did you come to read Schulz and what drew you to this text in particular?

I have to thank Prof. Lukasz Wodzyński for that- we had a wonderful graduate seminar “Modernism and Time” with him during my first year in the program. Along with Russian modernist literature, we read many polish texts, and this was almost entirely new to me and captured my interest immediately. I was particularly fascinated with Schulz, both his style and what I would call his highly peculiar awareness of historical time, its “materiality.” I just could not stop thinking about one of the texts we read, and I ended up writing a paper on it, which later evolved into the article. I also took Intensive Polish around that time, and I so much wanted to work with the original that I was able to do it quite soon- for this part I should thank Dr. Ewa Miernowska (or Pani Ewa, as we all call her).

The title of Schulz’s text seem to prompt a psychoanalytic reading, but are there perhaps others reasons that you chose to approach your analysis through this lens?

Simply put, Sanatorium pod klepsydrq is very much a story about grief, the impossibility of letting go of the memory of loved ones. I had been interested in memory studies for quite a long time, and particularly in how memory can be mediated in literature and thereby shared. This story makes it all, again, almost “material,” highly visible. The narrator escapes to an imagined Sanatorium where his deceased father is still alive because time moves backwards. I tried to approach it as more than a solipsistic escape, however: it was more interesting for me to think how this ostensibly extremely self-centered text imagines selfness and otherness together through testing literature’s form-giving capacities. In this article, I worked with the Freudian and post-Freudian theories, focusing on the gradual “depathologization” of the melancholic memory: how it came to be seen as a powerful and potentially reparative cultural mechanism. Now I am particularly interested in the political aspect of melancholia (left-wing melancholia above all)- how it becomes a perpetuum mobile of modeling alternatives, roads not taken, even when they seem to be entirely lost. So, it all started with this psychoanalytical perspective, but then it prompted new questions that seem highly relevant now, in this prolonged state of emergency, and I plan to approach them beyond this initial framework.

Does this article hint that you’ll be conducting more research on Schulz- or, more generally, on Polish Modernism-in the future? Are you heading in the direction of a Russian-Polish comparative dissertation?

Polish Modernism still fascinates me, and I am thinking of different ways in which I could build on my research, also engaging with other issues I am currently interested in. With Schulz, I would definitely pay more attention to the Polish-Jewish context, in which, of course, the Schulzean melancholia is deeply rooted. Currently, I see it more as a side project, but I would also say that maybe it is the principle that matters most here: a comparative approach is essential to what I do as a “beginner Slavist” now. In my dissertation, I will definitely work with both Russian and Ukrainian literatures, and I consider including Polish texts as well. Whether this will be part of my dissertation or a side project, I think that it is one of the greatest opportunities that we have as graduate students to explore, experiment, and cross boundaries. So now I see it as a symbolisms rather than ironic that, through I had worked primarily with Russian material before, my first publication in English turned out to be on a Polish text, to which I just immediately felt truly connected.